15: The New Nordic Boys Club

A chronicle of the things (and people) left out of a definitive culinary moment

Hi there,

I originally thought I’d introduce this issue with a breezy little metaphor involving the history of obstetrics and the ways in which kitchen tweezers resemble forceps. But the piece itself turned out to be so sprawling that I thought it best not to test your patience (and luckily my metaphors will keep).

So let’s get right to it. This is a story about the origins of the new Nordic manifesto and the controversy it provoked at the time. It is quite possibly a story you haven’t heard before--I know I hadn’t until Lars Bjerregaard mentioned it in one of our first conversations about Bord. And from parliamentary debates to counter-symposia, from the male chefs who “didn’t know shit about biodiversity,’ to “bullshit” justifications about women chefs, it holds some surprises.

This issue of Bord is available to everyone. But if you appreciate this kind of writing, I hope you’ll consider subscribing.

Thanks for reading,

Lisa

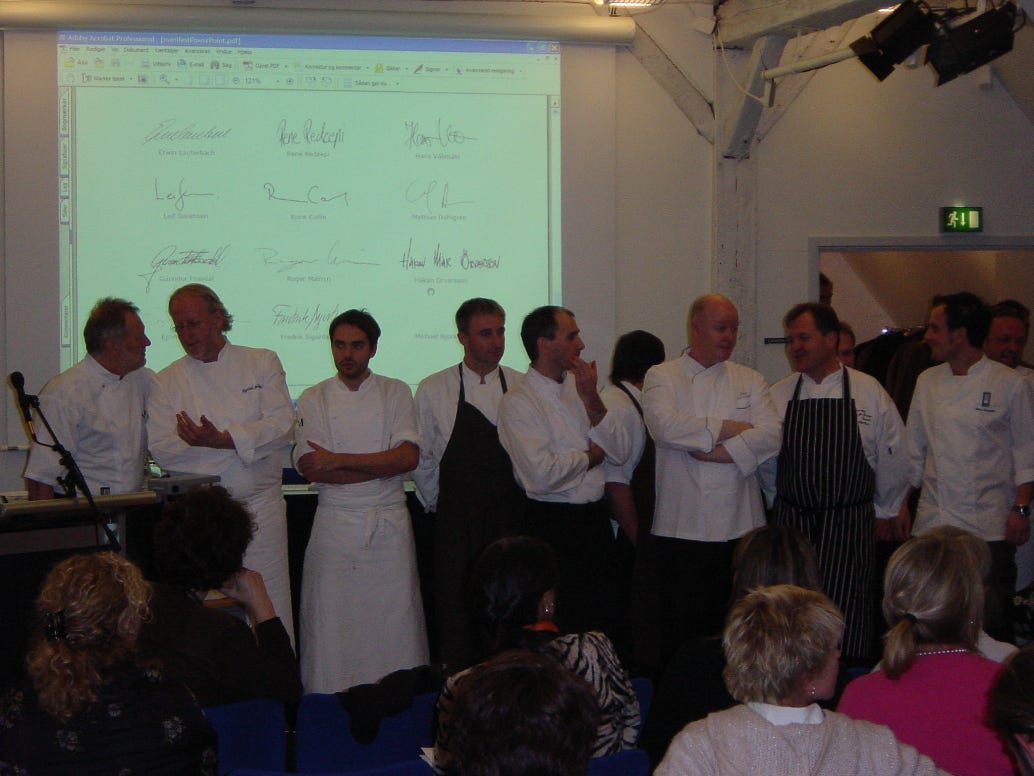

In the photo that Lise Lykke Steffensen took that day, no one looks like they’re making history. Clad in their white jackets, the chefs stand in an awkward scrum before the audience, none of them sure of where to place their hands or direct their gaze. Certainly no one seems to be looking behind them, where projected onto the kind of screen you might find in a sixth-grade geography class, are the twelve men’s signatures. But the document they have just signed is the New Nordic manifesto, and with it they have changed both the fate of cuisine in the Nordic countries and the course of gastronomy itself.

The story that is told about that moment has been recounted so many times and is itself so potent—the deliberate creation of a cuisine where none existed before, the launch of a trajectory that would catapult the region’s restaurants to the upper echelons of the gastronomic world and turn the region into one of the globe’s great culinary destinations— that many of us think we know it. But in its transformation into a foundational myth, there’s a lot about the origins of the New Nordic movement that has been left out. Or to be more specific, a lot of people.

Of the twelve chefs from six countries and two semi-autonomous regions who gathered on November 17, 2004 to sign the document that would launch a movement, not one was a woman. While it might be tempting to chalk up that absence to simple oversight in a less enlightened age, the truth is that even at the time, the gender imbalance provoked a controversy so pronounced that it would eventually pull in high-ranking officials in the Danish government--and a future prime minister. And although the absence has been largely left out of the story told about Nordic food, the repercussions of it still linger.

The manifesto was intended to serve as a touchstone for Claus Meyer’s larger project, which was to generate in Denmark and the Nordic region the kind of food culture he had encountered and appreciated in France, Italy, and Spain. Noma, which he opened in 2003, would act as the showcase for the project, but Meyer, a television chef and culinary entrepreneur who already had several businesses under his belt, also wanted to achieve a broader impact than one restaurant alone could provide. Together with Jan Krag Jacobsen, a journalist and consultant specializing in food, he began working on a symposium devoted to what he called New Nordic Cuisine. The plan, as he would later describe it, was to forge a “broad collaboration to create a regional food culture in Denmark and in the rest of the Nordic region, which could stand among the most beautiful and robust in the world.”

The Build Up

To organize the symposium, Meyer put together a steering committee made up of himself, three academics from the Copenhagen Business School—philosophy professor Ole Thyssen and researchers Lonnie Svarre Hansen and Gitte Holler (who would act as project leaders)— and a representative from the Nordic Council who specialized in agriculture, forestry, and food policy, Lise Lykke Steffensen. The committee invited speakers who included government ministers, leaders from the food industry, farmers, researchers, Carlo Petrini from Slow Food and the Spanish chef Andoni Luis Aduriz. They also decided to invite a small cohort of the region’s chefs to meet separately and hammer out the details of a declaration of intentions—a kind of mission statement— for what this new movement would look like. Two chefs from each of the Nordic territories, intended to represent two generations of cooking, were invited; the decision about which chefs to invite, Meyer would later write, was his “full responsibility.”

The idea for a culinary manifesto had long roots. Meyer was inspired by the Basque chefs behind the Nueva Vasca Cocina movement who signed their own manifesto in 1977, and those chefs, in turn, had been inspired by the “10 Commandments” for Nouvelle Cuisine that Gault et Millau published in 1973. But another source of inspiration came from home. In 1995, Danish filmmakers Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg had launched their own manifesto (which they entitled a “Vow of Chastity”) and with it, launched Dogma 95, an aesthetic movement that embraced a more naturalistic style of filmmaking.

To come up with the draft that they would bring to the chefs’ workshop, Meyer and Jacobsen consulted with a wide variety of stakeholders in the months leading up to the symposium. “The hard work was done by my mentor and myself in conversations with maybe 50 people,” Meyer recalls. “And of that, maybe 30 or 35 were women. That’s a detail that tends to be forgotten--there was female dominance in all the conversations that helped us produce a manifesto because women tended to be more concerned about the things we were concerned about. These male chefs didn’t give a shit about biodiversity or sustainability-- they couldn’t care less.”

Lisa Lykke Steffensen was one of the women who did care about those things. As she recalls, it was she who first alerted Meyer--even before he opened Noma--to their importance. Because of her involvement with Slow Food and her work at the Nordic Council (as part of her responsibilities, she oversaw the Nordic Gene Bank), she had a deep professional knowledge about biodiversity. When Meyer first approached her with his idea for building something around Nordic cuisine, she was enthusiastic, and encouraged him to look beyond influencing high-end restaurant kitchens to the broader arena.

“We sort of taught him about all the different species and varieties and richness that you have in the Nordic region,” Lykke Steffensen says. “Because I had been involved with Slow Food for so long, and because I had this huge engagement with genetic resources, I understood the biodiversity of the region. But he knew nothing--he was so surprised when I told him about how many different varieties of apples we have in Denmark, how many different varieties of carrots.”

Meyer depicts his own experience with the subject differently, noting that through businesses he founded in the late 1980s and 1990s, he introduced Danes to biodiversity in both chocolate and coffee beans and had, by 2003, been a Slow Food member himself for many years. “After studying biodiversity in practice in France in 1983-84, where it changed my life, I went on to fight the lack of diversity in Danish agriculture/food industry with everything I had.”

Wherever he obtained the knowledge, Meyer was emphasizing the need to include to focus on biodiversity and terroir by the time he began explaining the upcoming symposium to the media in September 2004. “We really need to strengthen the diversity of the Nordic raw produce,” he told Airport magazine. “We have more than 700 different sorts of apples in the North, but you can only buy ten of them in the shops.”

Yet for Lykke Steffensen, who had joined the steering committee, Meyer still seemed too focused on restaurant cuisine. “He wanted it to be about the New Nordic kitchen because he was very much about the Mediterranean kitchen; he was always talking about elBulli and what the chefs had done in Spain,” she says. “But I told him I thought the concept should be much bigger. It's not just about the kitchen. It’s also about where does your produce come from, what are you eating, how do you meet around the meal. It's not just creating a new Mediterranean kitchen but in the Nordic countries.”

Other female food professionals also shaped the conversation over many of the manifesto’s principles. Camilla Plum, Katrine Klinken, Trine Hahnemann, and Anne-Birgitte Agger, among others, were all working in different capacities to promote organic food and agriculture, develop local products, and improve the food served in both public institutions and private homes, and they knew Meyer personally and professionally. “We were all working for something very important on the Nordic food scene,” says Klinken—herself a trained chef who was then consulting for the leading organic organization and writing cookbooks— of her female colleagues. “The ideas in the manifesto were pretty good and open minded--but they were also the values that we had been focusing on for a long time.”

When the names of the chefs who would decide the final version of the manifesto were published, those women were dismayed to discover that none of them--or any female chef—was included. “We were so angry,” says Klinken. “There had been so many people who had fertilized the soil, so it felt like a slap in the face.” It was the same for Anne-Birgitte Agger, even though she was delighted to learn of the ideas that would be embodied in the manifesto. “I had been working on this for so long, and it was like, finally, it’s time,” she says. “But then we heard there were no women.”

They began to organize. “Camilla Plum called me and said Claus Meyer is making a manifesto for the chefs,” recalls Hahnemann. “They want to change the everyday way we eat but they’re not including women food writers or women chefs or all those women who cook for hospitals and elderly homes and public meals. And then she said, ‘I want to do something about it. Are you in?’”

The Explosion

Hahnemann was, along with twelve other women working in food were. On October 29, they sent a statement to the Nordic Council denouncing their exclusion. “Since when has it become official Nordic policy to support men and ignore women and women's qualifications?” it began, before describing the gender makeup of both the manifesto and the symposium and concluding, “Where men meet, women must be silent. When something has to be done, the men have to take the lead, and the women stay at home - and cook.”

Plum and Klinken followed up that letter with an editorial in Politiken. “Hardened Vikings from the Nordic brotherhood gather to sing of noble deeds,” it began. “The basic idea is that all true development and innovation in Nordic cuisine takes place exclusively within the pots and pans of the chefs at star restaurants.”

In both pieces, the criticism was two-pronged. On the one hand, the women charged that by associating the manifesto exclusively with high-end chefs, the movement to improve food in the Nordic region—despite its professed goals— was actually privileging restaurant cuisine and not everyday food. “My problem with this whole thing is that Claus Meyer did not go out and write a Nordic manifesto to make better restaurants. He wanted to change food culture,” says Hahnemann. “But how are you going to change the food culture without women? Like it or not, we’re still the ones who cook more meals than men, both at home and professionally. How is that going to happen without us?”

They also took umbrage with the justification for the lack of representation: a criteria for excellence that, by default, sent a message that there were no women good enough to be included. “That’s what was so bad,” says Agger. “They used the words, ‘there’s no one better than these guys.”

The steering committee responded to the public criticism with its own statement to the press. Noting that Plum had been invited to the preparatory meetings for the manifesto but, after initially accepting, later withdrew, it also described its decision to focus on restaurant cooking as intentional. “The initiative to meet around a Nordic Cuisine Symposium originated in the restaurant kitchen,” it read. “It is our belief that the new cuisine arises here and not in everyday life or in hospitals.”

After the Politiken piece came out, Meyer published another statement, this time on his own. He noted that, “The women’s critique helps us focus on a relationship we’ve been aware of, namely that the Nordic restaurant scene has been dominated by men for the past 50 years or so. If you look at the Nordic restaurant guides you’ll see that the most respected and innovative kitchens are all led by men,” before again explaining his rationale. “We have chosen to convene the biggest and most respected chefs to ensure the potential of Nordic cuisine in the highest possible condition.”

The tumult was not confined to the press. Both the Nordic Council and the Danish government (which, along with the other Nordic countries, contributes to the Council’s budget) had made gender equality a focus. “I was the person who had to defend this and explain internally to the Nordic Council of Ministers how come we were giving our money to this,” says Lykke Steffensen. “It was something like 200,000 or 250,000 kroner, but even if it had been one Danish krone, [the gender balance] had to be 50%-50% or 40%-60%. That’s just simply in the DNA of the Nordic Council: gender-wise we are equal.”

On November 4, 2004, the issue reached the floor of the Danish parliament. MP (and soon to become Copenhagen mayor) Ritt Bjerregaard brought the question before the minister for Nordic Cooperation, Flemming Hansen. Hansen noted that women were members of the steering committee and that several had been consulted in the process of researching the manifesto, and justified the absence of female signers in the same language as Meyer. “The chefs selected to prepare the New Nordic Cuisine manifesto are chosen solely on the basis of gastronomic qualifications and Michelin stars. In that context, it is, of course, regrettable that there are not several female chefs in the Nordic countries who have achieved this recognition.”

The chair of the Danish delegation to the Nordic Council would call the lack of representation “stupid and embarrassing.” It would also be publicly criticized by the Social Democrats’ spokeswomen for gender equality— none other than current prime minister Mette Frederiksen. But the explanation that Hansen (and Meyer) gave ultimately held sway, and the workshop went ahead as planned.

“Bullshit,” says Hahnemann now of the justification that there were no good female restaurant chefs in the region. While no women chefs in the Nordic countries held Michelin stars at the time, some had in the past, and several others had been recognized with other awards. In Denmark alone, Anita Klemensen, who would in 2012 become the first—and to this day, only— Danish woman to receive a Michelin star, was heading the pastry section at Søllerød Kro, and had a dish nominated for the annual culinary competition, Årets Ret. Betina Repstock, who had already earned a reputation for herself at Rogeriet in Rundsted, had recently become head chef at Alberto K, where she was also nominated for Årets Ret. Although her husband Bo would get most of the credit, Lisbeth Jacobsen was co-chef at Restaurationen, which held a Michelin star from 1999 until 2004. And Mette Martinussen, who had opened her innovative restaurant 1.th in 2001 and was recognized by the Danish Gastronomical Academy for it the following year, had apprenticed for Meyer earlier in her career.

In the wake of the controversy, none of those women, nor others like Heidi Bjerkan in Norway or Titti Qvanstrom in Sweden, were invited to join the manifesto. But the issue consumed the steering committee for a while. “We were really troubled about it,” says project manager Svarre Hansen. “We had several days when it was the only topic. What I remember of the discussion is that it was like: Oh my God, that’s right. Of course, there should have been women taking part in the writing of the manifesto, and I think that later, Claus Meyer recognized that. But at the time, he said they were looking for who in the Nordic countries would have the most impact.”

In the end, the Nordic Council did not withdraw its support and Lykke Steffensen admits that she didn’t force the issue. “I wasn’t there saying we’re going to cancel the whole thing,” she says.“There was so little time, and the symposium was only a few days away.” But asked why the committee didn’t correct course and invite some women restaurant chefs after the controversy broke, she is clear: “Because Claus Meyer didn’t want to. He didn’t see the problem.”

In his own statement, Meyer rejected the notion that gender discrimination was in play, and implied that it was the protesting women who were guilty of sexism, not he. “Not even by exerting myself to the utmost can I see this project as a gender policy initiative. We are amazed to see women in 2004 describing care, love and respect for strangers as particularly feminine values and are disappointed with their urge to publish their account—even before the manifesto has been approved—not about its content but about the gender of the selected chefs.”

These days, Meyer says he would do things differently, but he defends his 2004 decision. “I have no problem empathizing with the women who felt [they were being devalued]. But that wasn’t the intention. It was pretty important that the extremely dominant male individuals from the different Nordic countries were around, because without resources or funding or any kind of real mandate go about creating the short of change that we succeeded in creating? So we could not leave out two-Michelin-star chefs and replace them with wonderful women from other types of cuisine.”

Yet only four of the chefs who signed the manifesto had Michelin stars (Dahlgren, Lauterbach, Välimäki, and Hellstrøm; Redzepi would get his first a few months after the symposium). And although some who lacked those accolades, like Rune Collin from Greenland and Hákon Örvarsson from Iceland, were among the best known chefs in their home countries, others, like Leif Sørensen, who had just moved back to the Faroe Islands after many years in Copenhagen and was in the process of opening his first restaurant, had not yet established major reputations.

Furthermore, the total number of chefs seemed to be mutable. The first press release about the symposium stated there would be eight signers--presumedly one from each of the Nordic territories. By the time the program was posted online in October 2004, that number had changed to nine (one from each except Denmark, which had two). And by the time the symposium actually took place, it had grown again: now there were 12 chefs in the group. They included Roger Malmin, who in 2004 left his position as a line cook at Bagatelle to work as sous chef at a hotel and then, in September of that year, became head chef at the well-regarded Craig’s Pub in Stavanger; Gunndur Fossdal who was chef at Glasstoven, the restaurant in Tórshavn’s Hotel Forøyar before Sørensen took it over and turned it into Koks, and Fredrik Sigurdsson from Iceland.

According to Meyer, the plan was always to include two chefs from each territory–a mentor and mentee who could represent “two generations” of cooking—and he says that everyone invited accepted. Lykke Steffensen, however, recalls that a few chefs declined, and whatever the case, there were certainly discrepancies between the number of chefs announced, and those who actually participated. Yet even after the controversy over women broke, no women chefs, not even ones with equivalent accomplishments to, for example, Malmin, were invited to participate.

On November 17, the chefs began their deliberations in a room on the ground floor of North Atlantic House. By all accounts, there was a lot of debate. Some of it was relatively light-hearted--“It was being called New Nordic, and Erwin Lauterbach, who had ridden that way for many years, wanted to know what was new about it,” recalls Sørensen. But some of it was more serious. Some of the chefs, for example, wanted to include a clause that would protect the rights of chef and waiter trainees. “That might have been important,” says Sørensen, “Because I think people are just as important as point 6 in the manifesto: To promote animal welfare and sustainable production in the sea and in the cultivated and wild landscapes. But no agreement was reached.”

In the chefs’ discussion, the man who, after Meyer, would, ironically, become most closely identified with the manifesto apparently spoke little, in part because it was Noma’s kitchen that was hosting all the cooking for the symposium. “René was in and out because he had a dual role: they used his kitchen and he had to organize a lot,” says Lykke Steffensen. “He was very idealistic, but many things were new to him as well, and he had a sharp learning curve. So I think he listened a lot, and just tried to get the most out of it. Between that and being the host and producing the food, I think that was more than enough for him.”

It took them eighteen hours of sometimes heated deliberation, but the chefs finally reached an agreement on the text. In the afternoon of November 18, they filed upstairs to the symposium hall and presented the manifesto, whose ten points ranged from a commitment to express the region’s “purity, freshness, and simplicity” to an intention to involve a wide range of stakeholders “for the benefit and advantage of everyone in the Nordic countries.” Then, at a gala dinner that night, they prepared a meal that showcased their region’s ingredients: Sørensen opened the meal with a dish featuring horse mussels and sea snails; Collin prepared the main course of reindeer; Örvarsson made a mousse for dessert from skyr; and the entire menu was paired with Nordic ciders, beers, and wines. “In the end,” says Meyer, “We got them to feel enthusiastic about the idea of being about more than Michelin stars and some sort of deliciousness competition.”

The Fallout

Ironically, some of the symposium’s success may have been due to the gender polemic. “The crazy point that I don’t think anyone’s aware of,” says project manager Lonnie Svarre Hansen. “Is that we actually had a hard time getting word out about the symposium, and it was very difficult to find people who wanted to come. Initially, we were having a hard time selling the tickets. But once the controversy broke, the symposium filled up.” The controversy certainly brought more media attention; Hahnemann and Klinken both attended and gave television interviews.

The exclusion would also motivate the women to launch their own symposium. On March 8--International Women’s Day--they held a day-long gathering in Copenhagen that they christened Oprør fra Maven, or The Belly Rebellion. In addition to speakers including politicians, farmers, food writers, and chef Darina Allen from Ireland’s Ballymaloe Cookery School, the 600 or so women gathered enjoyed music, performances, and a food bazaar. Only one man--television chef Nikolaj Kirk—was allowed inside. “I’ll never forget Camilla Plum barring the door and turning away even the cameramen and male journalists who showed up,” says Hahnemann. “She would tell them to turn around and go find a woman.”

Lykke Steffensen, who is today CEO of the Nordic Genetic Resource Center, acted as a bridge between the two events, and in addition to speaking at Oprør fra Maven, was able to get some Nordic Council money for it. (Oprør fra Maven would continue as an organization for several years, working, for example, to establish farmers’ markets in Denmark’s largest cities). She would also take the lead in building the Council’s own New Nordic program (it was she who titled it New Nordic Food, rather than New Nordic Cuisine) as it supported a wide variety of initiatives intended to develop and promote the region’s food culture.

All that, according to Meyer, is exactly as it should be: the manifesto was meant to be the start of a broader movement that others would run with. The signing of the manifesto “was more symbolic than anything,” he says. “The most important thing was that another 50,000 people mentally and spiritually came to work alongside the values of the manifesto. That was much more important than having Eyvind Hellstrøm sign it. We needed his signature to begin with, so we could have a game-changing impact. But after that, it was up to anyone else. We were a few people presenting a manifesto, an ideology, that then other people could turn into compost or celebrate or change.”

In the years following the symposium, New Nordic would indeed expand to a broader sector, supporting producers small and large, and generating enthusiasm at home and abroad for the region’s food culture. It would launch new businesses and new forms of tourism, support better agriculture, and earn international media attention for the region. And although there would later be some backlash against it, it is largely held up as a huge success.

Yet many of the women involved in the initial protest maintain that, as a movement, New Nordic failed in its key goal of improving the broader food culture in the region. “Of course it’s been good in some perspectives,” says Klinken. “But if you go into any hospital or elderly home or school, I don’t think you’ll find good food. And if you think about people's diet in the Nordic countries, not much has changed.” Including women who had worked in that sphere, she and the others remain convinced, may have altered that outcome. It also may have enabled younger women to see themselves in the industry. Today, Agger is director of Denmark’s Hotel and Restaurant School, where just 25% of entering students are female, and only 14% of the graduating ones are. “Even if there was just one woman chef on the manifesto,” she says. “She could have been a role model.”

For at least some of the restaurant chefs who participated—and for the many others who would adopt the principles of New Nordic later—the impact was enormous. “For me, the biggest thing was to be with so many committed people,” says Sørensen. “I came back to the Faroe Islands on fire. I started to find someone to fish for me, I studied all the old books about the Faroe Islands to find out what they had eaten. I was looking for plants and became one of the first to use seaweed because there was so little else at the time we could use.”

Would Hrefna Rósa Jóhansdóttir, after discovering the sort of tribe that Sørensen found, have returned to Reykjavik with a burning desire to explore the possibilities of Icelandic cuisine? Would Kari Innerå have gone home to Norway, as Roger Malmin did, inspired to work with farmers to improve the quality of local produce? Would Karin Andersson, a finalist in 2004 for Sweden’s Chef of the Year, have traveled the world as a Nordic Food Ambassador the way Michael Björklund, who won in 2000, did? Would their presence at the foundational moment of what would become an important network have meant that women chefs from the region would also have been invited to participate in influential events like Looking North in 2007 or Cook It Raw in 2009 or MAD in 2011? And if any women working in food had been part of that group, would they later have had more opportunities, more funding, more influence, more prestige?

It is, of course, impossible to know what, if anything, the impact would have been. But in the story of the New Nordic manifesto and the controversy it sparked, there’s a lesson. In explaining why he wasn’t thinking about gender inclusivity in 2004, Meyer, like Redzepi and Sørensen, says now that “it was another time.” And it’s true: it was another time, one in which the concern with equality had nowhere near the prevalence that it does today. Yet even if the manifesto’s organizers and participants hadn’t recognized the gender issue going into the project, they certainly learned about it over the course of the controversy. If they then chose not to act on that knowledge, it was because they could. Just as we—even those of us who thought we knew the New Nordic story—could leave out that part of it.

Yet times change, and the things that some were free to ignore change too. Asked if he would do it differently today, Meyer says the answer is easy. “It would have been even more perfect if we had had an equal number of men and women around the table. I am 100% sure that the conversation would have been improved.” Redzepi goes even further. “Thinking about the question, I keep wondering what would it have been like if there were more women there, if it was 50-50? How would Copenhagen look today? It might have changed things for the better.” He pauses as if running scenarios in his head, then continues. “So my answer is this: I think we need to do it again. A new symposium and a new manifesto, for a new time.”