Giving it Away, Part 2

What medieval guilds, private culinary schools, and a very young Tony Bourdain have to do with today's stagiaire system

Hi there,

This was one of those weeks when events in the wider world—the repeal of Roe v Wade, the shootings in Oslo, the war in Ukraine, and, oh, the global retreat of democracy and looming threat of climate change—prompted one of my now-periodic existential crises. Because, let’s face it, given the general collapse of civilization, writing about restaurants can seem…inadequate. And yet, I don’t know what choice any of us has except to keep living our lives and trying to find meaning in the work that we do. Also, drinking wine in the sunshine helps.

So, onward: This week, Danish media stepped up the pace of their reporting on work conditions in Copenhagen restaurants. The podcast Den Uafhængige (The Independent) had interviews on the subject with Melina Shannon-Di Pietro, the executive director of MAD Academy (in English), and with restaurant critic Søren Frank (in Danish). The national newspaper Politiken ran a bit of self-flagellation for not previously covering the story better. But the biggest revelations came from Weekendavisen, where journalist Jeppe Bentzen published a story about some restaurants getting around visa requirements for non-EU chefs by surreptitiously taking back some of the salary they agreed to pay. I’ve got a feeling this piece is going to continue to play out for a while, so if you want to read up on what the conditions are for foreigners trying to work in the Danish restaurant biz, you may want to check out past issues of Bord here and here.

As for me, I’m picking up the discussion on stagiaires. Last time, I tried to lay out the general parameters of the problem: that stages are valuable to a lot of people who undertake them, but they can also be exploitative, and that there is something problematic about a business that cannot exist without the free labor stagiaires provide. If you’d like another take on this question from an international perspective, check out the piece that Nicholas Gill wrote for his excellent newsletter New Worlder, on cuisine in the Americas.

What I want to do in this essay, the second in what will be a 3-part (maybe 4? Once I get going, anything is possible) series, is to look at the stage’s origins and how it has changed over time. The story involves, among other things, the medieval guild system, Tony Bourdain, and the rise of the private culinary school, and even so, I’m sure I haven’t come close to touching on all aspects of it. But my hope is that by sketching out what I see as the general trajectory, it might provide a foundation from which people can think about which aspects of the system are valuable and worth keeping, which aspects demand change, and how we might go about achieving both.

One last thing: I should probably clarify some terminology. There are a lot of words to describe what is a temporary training period in which a usually young person without loads of experience works in a professional kitchen for low or no pay: stagiaires, apprentices, trainees, interns, externs. Some people or institutions differentiate among the terms (e.g. stagiaires are on short visits of a few days or a week whereas apprenticeships last months or years) but I’ve seen so much overlap that I’m going to use them interchangeably. Except for the word ‘extern’: I’m not going to use that one at all.

Thanks for reading. And keep the faith,

Lisa

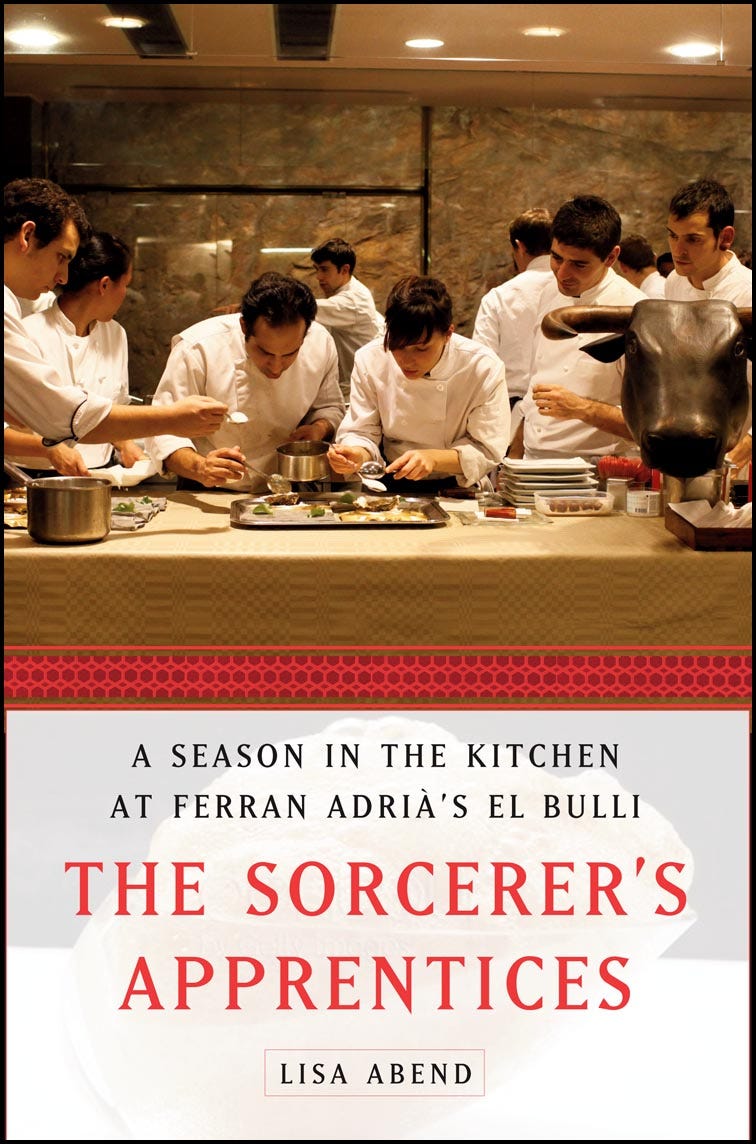

Over a decade ago, I wrote a book about the stagiaire system. It focused on the Catalan restaurant elBulli, which at the time held the top spot on the World’s 50 Best Restaurants list and three Michelin stars, and it described many of the exact same practices that have generated outrage in the Financial Times story. Fourteen to sixteen-hour days, five or six days a week. One 30-minute break per day, and no chatting in the kitchen outside of that. Stagiaires who couldn’t afford to buy food for themselves on their days off. Staff who were encouraged in ways subtle and not to work through sickness and injury. And all this, for a bed in a shitty apartment and exactly no pay. In fact, at elBulli, the stagiaires even had to pay to attend the staff Christmas dinner that the restaurant held to celebrate the end of the season.

And yet, young cooks from around the world applied for stages there in droves. ElBullli was then and remains to this day one of the most influential restaurants in history, in large part because it embraced a kind of radical creativity in the kitchen. It not only invented new dishes and techniques (though it did that with startling regularity), but questioned the very foundations upon which haute cuisine rested. Why does sweet come after savory? Why does a cocktail have to be liquid? Why is ice cream cold? When I once asked him what he learned from his own stage at elBulli, René Redzepi summed it up in one word: “liberation.”

It was the opportunity to learn that kind of creativity (and, to a lesser extent, because they knew that having elBulli on their CV would be a boon to their careers) that led over 3000 candidates to apply for stages in 2009, the year I was there. The 32 who were accepted into the 6-month, full-season stage (others would spend a week or two or just a few days) came knowing that they would not be paid for their work, but believing the sacrifice worth the education and experience they would get in exchange.

The Medieval Apprentice

For most of history, that has been the stagiaire’s bargain. The stage system dates all the way back to the Middle Ages, with its roots in the medieval guilds that acted as kinds of branch associations for various crafts and trades, from carpentry to goldsmithing to baking. Under the guild system, an aspiring craftsperson was required to undergo a long apprenticeship, which meant that from a very young age–often before they entered their teens— they were more or less indentured to a master craftsperson. The apprentice would live in the master’s home and eat at their table but would not be paid for the long hours of what was mostly grunt labor. Over time though–most apprenticeships lasted between 2 and 7 years– they learned the craft.

Although the guild system went the way of feudalism centuries ago, the apprenticeship remained the primary form of educating chefs well into the 20th century. In 1949, at the ripe age of 13, Jacques Pépin began his apprenticeship in the kitchen of the Grand Hotel d’Europe. As one of three stagiaires, he worked seven days a week, from 8:30 until 23.00, with four days off at the end of each month. He got a bed and meals, but no pay; the only income he had was the little money he managed to make catching frogs and crayfish during breaks and selling them to restaurants.

Twenty or thirty years later, the apprenticeship had been formalized in France and Switzerland, but the work conditions had hardly changed. Chef trainees still worked for free in restaurants from a young age (during the two years that Jean-Georges Vongerichten apprenticed at the Auberge de l’Ill, for example he worked from Tuesdays at 8 am until Sunday after lunch, and lived in a room above the restaurant that, along with meals, was his only compensation). But now, an effort was made to ensure they got a somewhat broader education– apprentices had to attend classes one day a week and pass an exam before they could get ‘real’ jobs.

In fact, by the late 1970s and early 1980s, culinary schools were starting to become a more common route into the profession, and that would change the nature of the stage. Most culinary schools required (and continue to require) some kind of internship (or, as they are confusingly called in the US, externship) in a restaurant as a condition for graduation. But these internships were seen as a supplement to the school’s education and not a replacement for it–sort of a finishing school, rather than school itself. The stage became much shorter as a result, though other conditions didn’t change. As one of the most talented students in the culinary program at a vocational school in Perpignan, Eric Ripert got what was considered the plum internship at a supposedly ‘gourmet’ restaurant in 1980. It meant working six days a week peeling potatoes and boning anchovies from 8:30am until midnight, and beyond meals and a bed in a ‘rathole’ of a room, he was not paid. But at least his stage lasted only two months.

Somewhere in there, it also became normal for young chefs to do quick, fly-by stages in top kitchens just to get a feel for how they operated (and maybe get “inspiration” for a few recipes). Ferran Adrià, for example, actually started at elBulli as a stagiaire, spending a month in the summer of 1983 there during his summer break from his military service. After he returned the following year, he did a 2-week stage at Georges Blanc in 1985 and another–by then he had become head chef—at Restaurant Pic in 1986. Years later, Grant Achatz would stage for about a week at Adrià’s restaurant.

The (Formally) Educated Apprentice

Something else started happening in the waning years of the 20th century: cooking became cool. There are a lot of broad social reasons for this, including rising prosperity, expanding notions of art and culture, and the emergence of entire networks devoted to food programming. But there was also one very concrete one: the publication, in 2000, of Anthony Bourdain’s Kitchen Confidential, which brought new allure to the hard-working, boundary-breaking, smack-talking (and taking), “pirate ship” of the kitchen.

In the book, Bourdain describes his crew as comprised almost entirely of ex-cons and high school dropouts, but he was working the line in what was, by his own description, a pretty middling bistro. In more renowned restaurants up until this point, chefs still tended either to be born into the business (Alain Chapel, Anne-Sophie Pic, Michel Bras, Pierre Gagniaire, Paul Bocuse, Juan Mari Arzak, Thomas Keller) or come from working class backgrounds (Robuchon’s dad was a brickmason; Alain Senderen’s was a barber; Michel Guerard’s parents ran a butcher shop; Ferran and Albert Adrià’s dad was a plasterer; Alex Atala’s a factory worker).

But as cooking became cool, the social composition of the group of people doing it started to change. The kitchen began to attract aspiring chefs from the middle and upper middle classes: people whose friends went to university to become teachers or CEOs or lawyers, people whose parents would never have considered cooking as a legitimate career for themselves (and who were, in some cases, appalled at the thought for their children); people who considered themselves ‘creatives.’ And although there were still plenty of chefs from more humble backgrounds, the field broadened: Enrique Olvera, Dan Barber, and David Chang are all the sons of businessmen; Daniel Humm of an architect; Amanda Cohen is the daughter of a surgeon.

And as the demographics of the profession changed, so too did the methods for training people in it. Until this point, the few private culinary schools that existed devoted themselves primarily to training housewives to become better home cooks. But around the 1970s and 80s, these same schools sought to remodel themselves as elite institutions that would appeal to middle-class students who had grown up with the expectation they would seek higher education. The Culinary Institute of America is perhaps the best example of this; in 1972 it moved into a grand former monastery in the Hudson Valley with serious Ivy League vibes (which may be why Bourdain, who attended a few years later, chose it after dropping out of Vassar). But at least some of the same impulse toward training aspiring chefs who come from more prosperous families and a more educated background can be seen in the Institut Paul Bocuse, Le Cordon Bleu, ALMA, and the Basque Culinary Center, to name a few.

That both public and private culinary schools facilitated and in many cases required internships for their students seems pedagogically sound–anyone who has stepped foot in a restaurant kitchen can tell you that it bears little resemblance to what goes on in even the most lifelike classroom. But it also had the effect of reinforcing the unpaid apprenticeship in new ways.

The Mutually-Beneficial Apprentice

For one, it meant that stages were no longer entirely voluntary–at least not for those students who wanted to graduate from schools, like CIA, that require them (at others, like Cordon Bleu, it is optional). It would also cement a mutually beneficial relationship between restaurants and culinary schools. For restaurants, an arrangement with a culinary school or schools enabled them not only obtain a steady supply of apprentice labor but also opened avenues for obtaining visas for foreign trainees and, in some cases, legally avoid paying them since the work was being performed for “educational” purposes.

It also benefited the schools. For private schools in a highly competitive market, the promise of an internship in a well-regarded restaurant became a powerful tool for attracting students. And so much the better that they could still charge at least partial tuition for the months or semester when the student is interning. At Le Cordon Bleu, an internship raises the tuition from 29,600€ to 32,100€. At CIA, the three credits a student earns during their semester-long internship come with a fee of $3300. At Institut Paul Bocuse, there is no separate fee from the 12,600€ annual tuition, but students must work a 4- to 6-month internship during each of the three or four years they attend. At the Florence Culinary Arts School, 2 months of coursework followed by 4 months of staging costs 11,400€ tuition; the price goes up by 1000€ if the student chooses a 10-month stage instead. In other words, many of these students are not only not being paid to work, they are themselves paying for the opportunity.

The situation in public schools is somewhat different. In Denmark, for example, student apprenticeships are paid, though this law applies only to domestic positions; if a Danish student seeks a stage abroad, for example, they are no longer guaranteed a salary for it. In France, stages are worked into the curriculum, and restaurants are supposed to pay interns a “stipend” of 3.90 euros per hour—although this is only true if they work at a place for more than two months.

It would be nice to think that association with an educational institution guarantees greater oversight over work conditions, but it’s not clear if this is true. Many schools require restaurants and other companies to apply for the opportunity to host interns. At CIA, for example, a potential employer must fill out an application that includes a training plan for the student. Yet although the school notes that “these students will be employed full-time in your kitchen and will be contributing to your bottom line,” it does not require but rather “requests” that employers “pay at least minimum wage.”

I’ve had conversations with chefs in the US who reported harassment and other kinds of mistreatment to their schools but received no response from their administrations. And here in Denmark, where workplaces must be approved before they can accept interns, students have filed hundreds of complaints against the restaurants and canteens where they interned. Yet according to the Danish union newspaper, Fagbladet 3F, the last time an employer had their approval revoked was in 2008.

So where does this leave us? Hopefully, this little foray into the system’s history has illuminated how thoroughly the often-unpaid apprenticeship is baked into the process of training chefs, even as that process has changed over time. But it’s not just the changing approach to culinary education that has gotten us the system we have today. Something else changed, at the level of cuisine itself, that deepened restaurants’ dependency on stagiaires. It was a transformation that, like so much of contemporary gastronomy, was hugely influenced by elBulli, but it did not originate there.

For that, I blame Joël Robuchon.

(My reasons, in Part Three)